A priority for the National Adoption Service for Wales (NAS) is ‘healthier contact through better birth family services’. An audit was carried out at the end of 2022, to gather quantitative and qualitative information from a range of professionals working with adopted children and their families.

An adopted child’s identity will always encompass multiple elements and a child’s long term psychological and mental health depends on finding answers to fundamental questions about who they are. All children looked after will have a contact plan, including those to be adopted. This can be either direct/face-to-face or indirect (e.g., ‘letterbox’[1]). For many years indirect contact has been the default, with a relatively few children having any form of direct contact.

The NAS Good Practice Guide on Contact (2019) outlines the principles and elements of best practice. It states:

… proposed contact arrangements…. should always include an exploration of the possibility of direct contact both to identify who is significant to the child, and in order to ascertain needs and services required to meet these now and in the future.

All prospective adopters are asked to commit to some form of contact but the agreement that they sign is not legally binding and although contact orders[2] can be made, they are exceedingly rare. As implied above, needs in relation to contact will inevitably alter over time as the child develops and individuals’ circumstances change. Thus, periodic review and ongoing support are needed.

Quantitative results

The quantitative information from the audit provides a useful benchmark to measure progress against. In 2021/2022, 230 children had a Placement Order[3] in Wales. Each had a plan for some form of contact, but only 15% included direct contact.

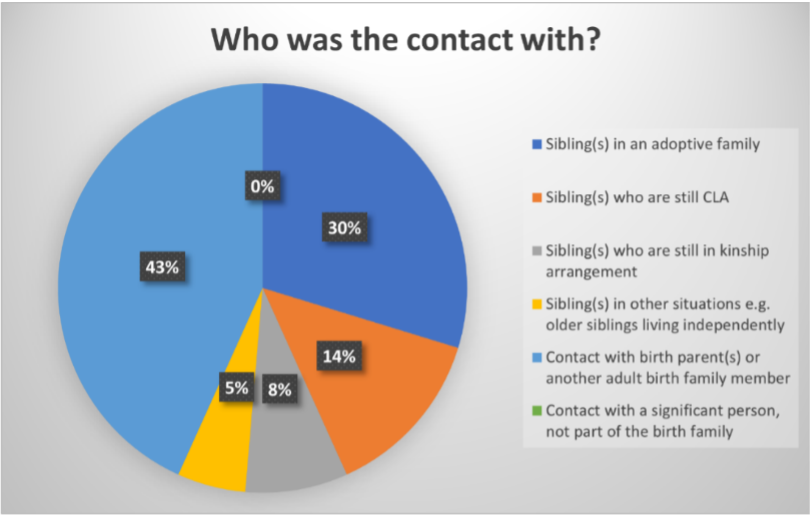

Meakings et al. (2018) found that none of the families in their sample from 2014/2015 had a plan for face-to-face contact with birth parents. Jones, MacDonald and Brooks (2020) looked at rates of post adoption contact across the UK. It found that, ‘Adoptive parents in Wales reported the lowest rates of direct contact at 16%’, which aligns closely with the figure from this audit, while Northern Ireland reported the highest at 54%’. While the proportion of children have direct contact is still relatively low in Wales, this provides evidence of progress. Each year the number of contact arrangements pre-18 has increased. The audit showed that currently there are 5070 contact arrangements in Wales but managing/supporting these requires significant resources. Approximately 20% become dormant over time for a variety of reasons.

Qualitative results

Planning

Participants felt that when decisions about contact involved adoption professionals and drew on research, it generally led to a more flexible and nuanced approach, rather than a standardised/formulaic response, based on longstanding custom and practice. Any issues were generally to do with deficits in planning and communication.

The importance of support

Good support was seen as the key to sustained/meaningful contact with a consistent point of contact for birth family and adopters who specialised in this area of work. Clear guidelines and information are needed, but also relationships that build trust between the participants and professionals.

Supporting birth parents can be particularly challenging:

Letterbox starts at the point when they are at their lowest ebb – they are angry and grief stricken – taking time to establish a relationship with them when the family finding social worker is in the midst of family finding and then managing the transition is challenging and needs a lot of time and work and this is usually the work that suffers when having to prioritise.

Meetings between birth parents and adopters

The NAS priority of ‘Healthier contact’ includes ‘a presumption of initial meetings between adopters and birth parents unless there is a compelling reason for this not to take place’. These are often referred to as ‘one-off meetings’, but ‘initial’ or ‘introductory’ meetings’ may be preferable. Respondents said they can help those involved to start the process of building trust and to see each other as ‘human’. The ability to empathise is seen as vital for contact to be sustained, meaningful and thus beneficial for the child.

The total number of such meetings represented 18.6% (61) of the children placed. Of these 80% (49) took place around the time of placement and 20% (12) more than 6 months after placement.

Inflexibility over the timing may limit the number of such meetings. They typically take place around the time of introductions/placement and the possibility of later meetings may be discounted. Some respondents felt that the quality of interactions may be better if meetings are later and other options including virtual meetings should be considered.

A positive approach to contact at an early stage through preparation training and encouragement of and support for ‘settling in letters’ was also highlighted as important for long term success.

Direct contact

Although numbers are small, direct contact may be taking place, which agencies are not aware of. It is still regarded as exceptional and often discounted because of perceived risk, but there is little evidence of systematic assessment of risk vs potential benefits. Some practitioners have little or no experience of direct contact and may assume that it is intrinsically unsafe or unhelpful.

In 2021/22 there were 7 unplanned contacts via social media. There may be others that were not reported. Many respondents are concerned about this and would like more information and support. 35.5% said that specific training was available from their service, 47% that general advice was provided. Such contact seems inevitable, and families need to know how to manage and minimise the risks.

Reviewing contact arrangements

It is important to review all types of contact and ensure that it is still appropriate to the needs of the child. Children will grow and develop; birth parents may respond to the loss of their child by making significant changes and adoptive parents are inevitably affected by their child’s development as well as changes in their own lives. Respondents reported considerable variation in arrangements for review, whether systematic, in response to a change in circumstances or at the request of an individual.

Overall conclusions

Overall, there is evidence that contact is seen as being extremely important by all those working with adopted children and their families. Progress has been made in developing practice, but there is still much more to be done. Continued levels of openness and flexibility in planning for contact, particularly in terms of consideration of direct contact are needed. Resources to support all concerned and likewise to enable systematic review of arrangements will also be crucial to arrangements working well as we go forward.

By Chris Holmquist,

[1] Letterbox contact is a voluntary arrangement where adoptive parents and birth families agree to keep in touch by exchanging news via the adoption agency responsible for placing the child, once or twice a year. Normally this would cease when the child becomes legally an adult at the age of 18.

[2] Contact Order – Section 9 of the Children and Families Act 2014 inserts a new section 51A into the Children Act 1989 to make provision for the Court to make an order to allow or prohibit contact between an adopted child and a specific and restricted range of people.

[3] Placement Order – an order made by the court made under Section 21 of the Adoption and Children Act 2002, authorising a local authority to place a child for adoption with any prospective adopters who may be chosen by the authority (subsection (1)).

This Blog is part of our ExChange conference, “Reframing Adoption”

To find more resources on this topic, check out the conferences below.

sdasada